Florence B. Price

by Dr. Michael J. Cooper

Florence Bea(trice) Price was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, on 9 April 1887. She began learning music from her mother at an

early age and gave her first piano performance at age four, reportedly publishing a composition (now lost) at age eleven. She

graduated high school at the age of sixteen and in that same year was accepted into the New England Conservatory (Boston), then

as now one of the most prestigious musical academies in the U.S.

Florence B. Price Biography by Dr. Michael J. Cooper

More than any other instrument or ensemble, the piano was the primary outlet for Price’s inexhaustible musical imagination. It was the instrument on which she received her earliest musical education and it, together with the organ, was the focal point of her education at the New England Conservatory (Boston), where she completed two diplomas at the age of nineteen in 1906. It was the centerpiece of her music teaching at the Cotton Plant Academy (a large co-educational boarding school near Arkadelphia, Arkansas for Black Americans) from 1906 to 1910, and of her work as head of the Music Department of Atlanta University from 1910-1912. And she taught piano privately from 1912 until only months before her death in 1953 – not only to dozens of beginning, intermediate, and advanced students in Arkansas and her adopted hometown of Chicago, but also to her own daughters. Aside from the music she wrote for the instrument, one of the most telling (and charming) indications of the centrality of the piano to her identity as musician is an undated ink drawing found among the Florence Price papers in the Libraries of the University Arkansas, Fayetteville – a competent drawing, apparently in a youthful hand, of a piano in a domestic room of some sort, lid up, bearing the caption: MY CAREER.

Small wonder, then, that compositions for piano make up some 216 of Price’s total surviving output of 458 works – about 47%, more than any other single category, followed next by songs and arrangements of spirituals (all of which also include piano). Nor is it surprising that it was a composition for piano (the suite In the Land o’ Cotton, presented on this album) that secured her recognition as a composer – a tie for second prize in the Holstein Competition sponsored by Opportunity Magazine in 1926 – or that it was piano compositions that fueled her rising renown in the early 1930s: a Cotton Dance won honorable mention in the Rodman Wanamaker Composition Competition for Composers of the Negro Race in 1931; her Piano Sonata (included on this album) and fourth (B-minor) Fantasie nègre won prizes in the same competition in 1932; and her Piano Concerto in One Movement was performed three times in 1933-34: at the commencement exercises of Chicago Musical College and the national convention of the National Association of Negro Musicians (both of these with Price herself as soloist), and with the Woman’s Symphony Orchestra of Chicago at the Century of Progress World’s Fair in 1934 (this with Margaret Bonds as soloist). The Preludes included on the present album date from these early years, and in fact the only complete autograph of the set survives in the papers of Margaret Bonds now found in the Georgetown University Libraries (Washington, D.C.).

Florence Price’s style began to change in the late 1930s, more overtly embracing modernist idioms in addition to the Afro-Romantic ones that characterized her earlier works – but the piano remained her constant musical companion to the end, with lyrical gems such as the Three Roses and Your Hands in Mine and evocative masterworks such as Clouds, the Scenes in Tin Can Alley, and her final major suite, Snapshots, rounding out the compositional products of her lifelong love of the instrument. She was preparing to leave to receive an award in France when she was hospitalized in May, 1953. She died of a cerebral hemorrhage on 3 June – leaving behind a handful of published works and hundreds of unpublished ones that are only now beginning to become known.

Dr. Michael J. Cooper

Professor of Music

Southwestern University

Editor, collected works of Florence B. Price (New York: G. Schirmer)

Contributing editor, Margaret Bonds Signature Series (Worcester: Hildegard Publishing Company) Journeys (blog)

Author, Historical Dictionary of Romantic Music (Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow,2013)

Born: April 9, 1887 – Little Rock, Arkansas

Died: June 3, 1953 – Chicago, Illinois

Florence Beatrice (Smith) Price became the first black female composer to have a symphony performed by a major American orchestra when Music Director Frederick Stock and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra played the world premiere of her Symphony No. 1 in E minor on June 15, 1933, on one of four concerts presented at The Auditorium Theatre from June 14 through June 17 during Chicago’s Century of Progress Exposition. The historic June 15th concert entitled “The Negro in Music” also included works by Harry T. Burleigh, Roland Hayes, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and John Alden Carpenter performed by Margaret A. Bonds, pianist and tenor Roland Hayes with the orchestra. Florence Price’s symphony had come to the attention of Stock when it won first prize in the prestigious Wanamaker Competition held the previous year.

Dates: Born: April 9, 1887 - Little Rock, Arkansas

Florence Beatrice (Smith) Price became the first black female composer to have a symphony performed by a major American orchestra when Music Director Frederick Stock and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra played the world premiere of her Symphony No. 1 in E minor on June 15, 1933, on one of four concerts presented at The Auditorium Theatre from June 14 through June 17 during Chicago’s Century of Progress Exposition. The historic June 15th concert entitled “The Negro in Music” also included works by Harry T. Burleigh, Roland Hayes, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and John Alden Carpenter performed by Margaret A. Bonds, pianist and tenor Roland Hayes with the orchestra. Florence Price’s symphony had come to the attention of Stock when it won first prize in the prestigious Wanamaker Competition held the previous year.

The Chicago Daily News reported: “It is a faultless work, a work that speaks its own message with restraint and yet with passion . . . worthy of a place in the regular symphonic repertory.” Later it would become known through the archival records of Chicago Music Association (CMA) that Maude Roberts George, classical music critic for The Chicago Defender and President of CMA of which Price was a member, underwrote the cost of the June 15, 1933 concert.

A Fight for Recognition

Although this premiere brought instant recognition and fame to Florence Beatrice Price, success as a composer was not to be hers. She would “continue to wage an uphill battle – a battle much larger than any war that pure talent and musical skill could win. It was a battle in which the nation was embroiled – a dangerous mélange of segregation, Jim Crow laws, entrenched racism, and sexism.” (Women’s Voices for Change, March 8, 2013). The same fate would also befall fellow Arkansan William Grant Still, the “Dean of Black Composers” (whose Afro-American Symphony was performed by the Rochester Philharmonic Symphony under Howard Hanson, the first time in history that a major American orchestra had played a symphonic work by a black composer) and many others due to rampant endemic and systemic racism.

A Young Beginning

Professor Dominique-René de Lerma, distinguished American musicologist and eminent historian states “Florence Price was born in a racially-integrated community in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1887 where, at the age of four, she played in her first piano recital and her first composition was published at the age of eleven, all under her mother’s guidance.” De Lerma continues, “Her mother Florence Irene Smith Nee Gulliver, had been a school teacher in Indianapolis, Indiana before her marriage, and in Little Rock had a restaurant, sold real estate, and served as secretary of the International Loan and Trust Company. Her father, James H. Smith, was the city’s only black dentist (his patients included the state’s governor) who had moved to Little Rock in 1876.”

A Young Beginning

Professor Dominique-René de Lerma, distinguished American musicologist and eminent historian states “Florence Price was born in a racially-integrated community in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1887 where, at the age of four, she played in her first piano recital and her first composition was published at the age of eleven, all under her mother’s guidance.” De Lerma continues, “Her mother Florence Irene Smith Nee Gulliver, had been a school teacher in Indianapolis, Indiana before her marriage, and in Little Rock had a restaurant, sold real estate, and served as secretary of the International Loan and Trust Company. Her father, James H. Smith, was the city’s only black dentist (his patients included the state’s governor) who had moved to Little Rock in 1876.”

Price graduated as high school valedictorian at age 14 and left Little Rock in 1904 to attend the New England Conservatory and, after following her mother’s advice to present herself as being of Mexican descent, earned a bachelor of music degree in 1906, the only one of 2,000 students to pursue a double major (organ and piano performance) studying with Frederick S. Converse (piano), George Whitefield Chadwick (music theory), and Henry M. Dunham (organ). Dr. De Lerma states that it was about this time that Price “started to think seriously about composition.” Following graduation she taught for one year at the Cotton Plant-Arkadelphia Presbyterian Academy campus in northeastern Arkansas (the main campus was located in the southwestern Arkansas city of Arkadelphia) then at Little Rock’s Shorter College, and from 1910 to 1912 at Clark University in Atlanta before returning to Little Rock where she taught privately and became active in composition.

Before the Birth of Florence B. Price

The grandmother of Florence B. Price was named Florence Irene Gulliver Smith. Florence Irene was considered a mulatto woman. The term “mulatto” was used during the 1800’s and it referred to a child that was born to a black slave mother and a white slave master. It is considered an offensive term by today’s standards, but within the historical content of this article, it is used with respect to the history of Florence B. Price. Florence Irene’s mother was named Mary McCoy who was born in 1835. Read about the Gulliver family, the grandfather of Florence Price:

Before Birth

The McCoys were free blacks from North Carolina. They were a part of a very small percentage of blacks that were free during this time. They moved north before the Civil War for hopes of better opportunities of employment and education. Uniquely, everyone in the McCoy family could read and write.

The grandfather of Florence B. Price was named William Gulliver. Mr. Gulliver was also considered a mulatto. He was born in Virginia in 1831. He moved from Virginia to Indianapolis. The Gulliver’s eventually would own multiple barbershops. With such success during this period for blacks, the Gulliver’s were considered as part of the black middle class. Many slaves who had escaped from slavery in the South found work in Indianapolis and along with free blacks, would eventually make up the small population of the black middle class.

Mr. Gulliver met the McCoy family in Indianapolis and would eventually marry their daughter, Florence Irene Gulliver in 1854. Growing up in a middle-class home, Florence Irene, the mother of Florence Beatrice, was born into a beautiful home environment with the ability for her to have piano lessons. She had an aunt who was a dressmaker and another aunt who was a teacher which for some period of time, both would live with the family which meant that Florence Irene had strong black women as mentors as she grew up. Florence Irene became a teacher and taught Elementary school which included all courses and music as well. It is suggested that she may have been the only black teacher who was teaching in an all white school. As well, Florence Irene was an amateur singer and would become an accomplished pianist.

Parents of Florence B. Price

The father of Florence Beatrice, Dr. James H. Smith, was a dentist. His parents were free blacks. His parents were of mixed races. Dr. Smith was born in 1843 in Camden, Delaware. His parents eventually moved the family up to New Jersey with the hope of better living conditions. Though blacks were considered free there were many conditions that would prevent blacks from obtaining legal residence and were prevented from becoming politically active. New Jersey offered living conditions for blacks that were a little better. Dr. Smith moved to New York by the time he was 15 and found employment as a private secretary as he continued his education. Eventually he moved to Philadelphia to study dentistry. He worked as an apprentice but when he tried to apply to dental schools, he was denied acceptance because he was black. There were no black dental schools in the nation. He would continue his work as an apprentice until he received certification and was able to practice dentistry. This was an amazing feat because by this time less than a dozen black dentists existed in the United States. Read more about her parents:

Parents

Dr. Smith opened up his dentistry business in Chicago and became politically active in the black community. Unfortunately, the great Chicago fire of 1871 would destroy his business and home along with thousands of community members would lose everything. Over 100,000 people lost their homes and businesses. Many blacks would then move to Little Rock including Dr. Smith.

Dr. Smith married Florence Irene on November 15, 1876. They moved to Little Rock and began their family.

Growing up in the Smith’s Home

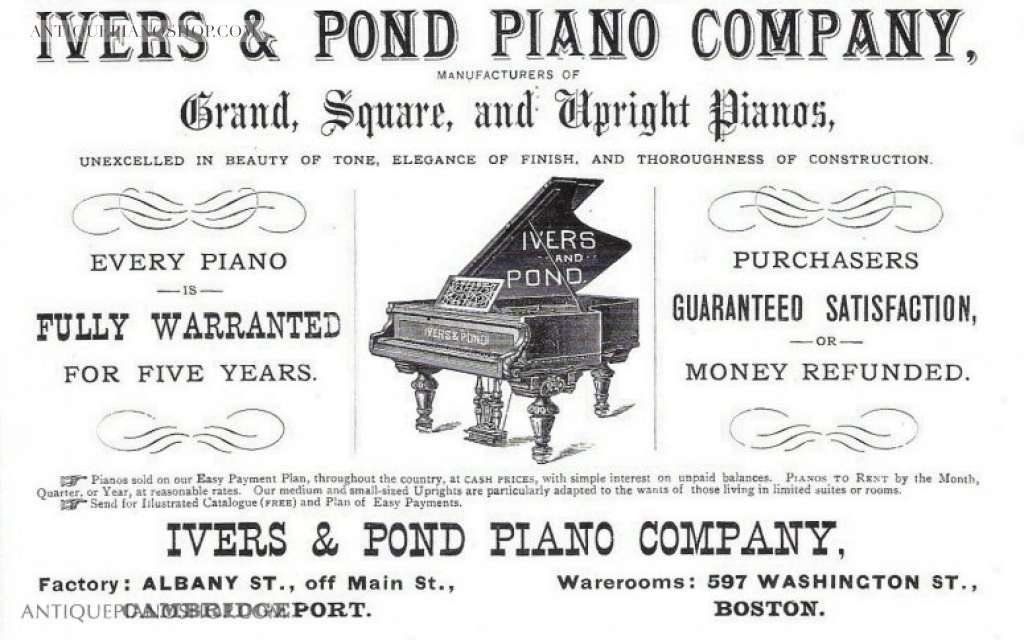

At the time of Florence Beatrice Price’s birth, April 9, 1887, the home was elegant and lavishly decorated. Dr. Smith had a very successful dental business with black and white clients. He was also very involved in the community and was politically active as well. Her mother, who was an accomplished pianist, regularly entertained guests and would often play for the guests. It was known that she owned a Ivers and Pond piano, a very expensive instrument made with exotic woods with beautiful ornate designs in the cabinet of the instrument. Click Read More to see an advertisement of the Ivers and Pond piano during the late 1800’s:

Piano

The Smith’s Home

Their home had such rooms as a formal library as there were no libraries for blacks. He owned many medical books and journals which Florence Beatrice enjoyed reading. They had carpeted floors, lavishly decorated parlor, a sewing room, a kitchen, and three bedrooms with walnut and oak furniture. Read about the famous guests that stayed in the Smith’s home by clicking Read More:

Home

Guests such as Langston Hughes, seen below, would stay with the Smiths.

John Blind Boone, one of the first black concert pianists to gain a national reputation stayed with the Smiths and would become a mentor for little Florence Beatrice.

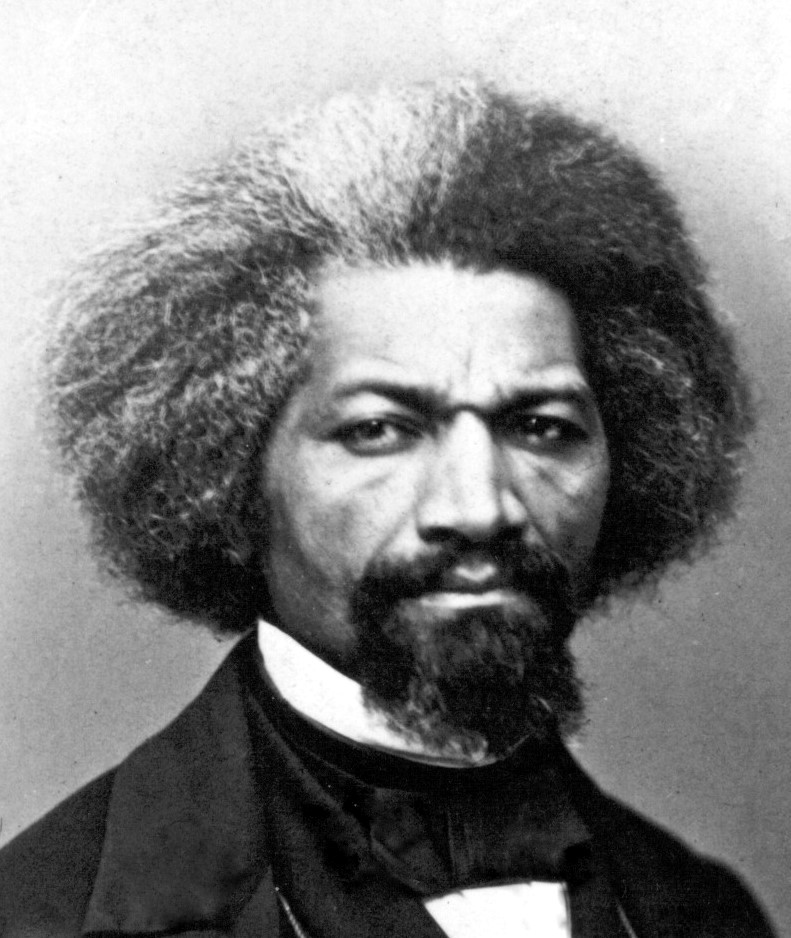

Frederick Douglass was another guest that little Florence Beatrice would meet at the tender age of two when he stayed at the Smith’s home.

At this time, there were only two black owned hotels in Little Rock during the late 1800s. Many would stay at the Smith’s home and other well to do black homes. One of the Smith’s neighbors were the Stills, the parents of William Grant Still, seen below, who grew up with Florence Beatrice.

Early Lessons and Composition

Early Piano Lessons

Florence Beatrice started piano with her mother well before the age of four because by the age of four she had played her first recital. Concert pianist John Blind Boone was in town at the time of her concert. He was very enthusiastic about her talent and would maintain a friendly relationship with Florence Beatrice for many years of her life.

Composition

Early Composition

She had completed and published her first composition by age 11. One of her teachers was Mrs. Charlotte Andrews Stephens, who had been educated at Oberlin and had returned to Little Rock to teach public schools. She proved to be very inspiration for Little Florence Beatrice.

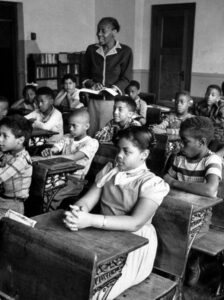

Secondary School Days

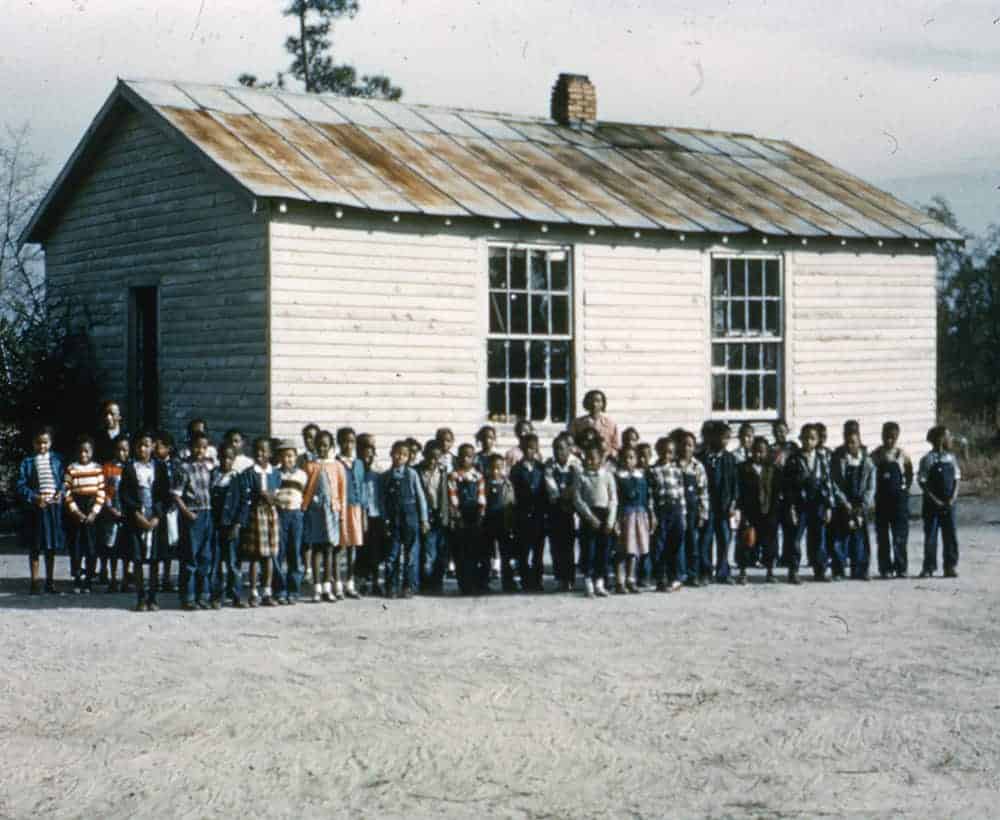

Florence Beatrice attended Union School which later became known as Capitol Hill High. Union School was at first an elementary school and a night school for blacks. Eventually it would expand to junior and senior school. Florence Beatrice enjoyed school and had such subjects as reading, spelling, writing, grammar, diction, history, geography, arithmetic, and music. Read about conditions of schools during the 1890’s for black students:

Secondary School

In 1896, racial segregation was allowed, separate but equal. (Plessy vs. Ferguson). Because most of the facilities that blacks had access to were far less funded than their white counterparts, most blacks did not have the education that would allow for them with whites and immigrants for jobs. The schools were understaffed, inferior books, but Florence Beatrice did not let that stop her. In high school, she studied Greek, Latin, algebra, history, physics, English along with painting, sewing, cooking among a host of other crafts.

An example of a one room school like the one Dr. Smith taught at is seen below:

High School

Florence Beatrice graduated from high school at the age of 14. She was valedictorian of her class. It was no surprise that she would graduate so early. Her mother focused on helping her daughter to develop leadership skills and helped her to develop a sense of organization. These would help Florence Beatrice in her later years in life as she would act as her own agent as well as keeping busy as a composer and pianist.

High School

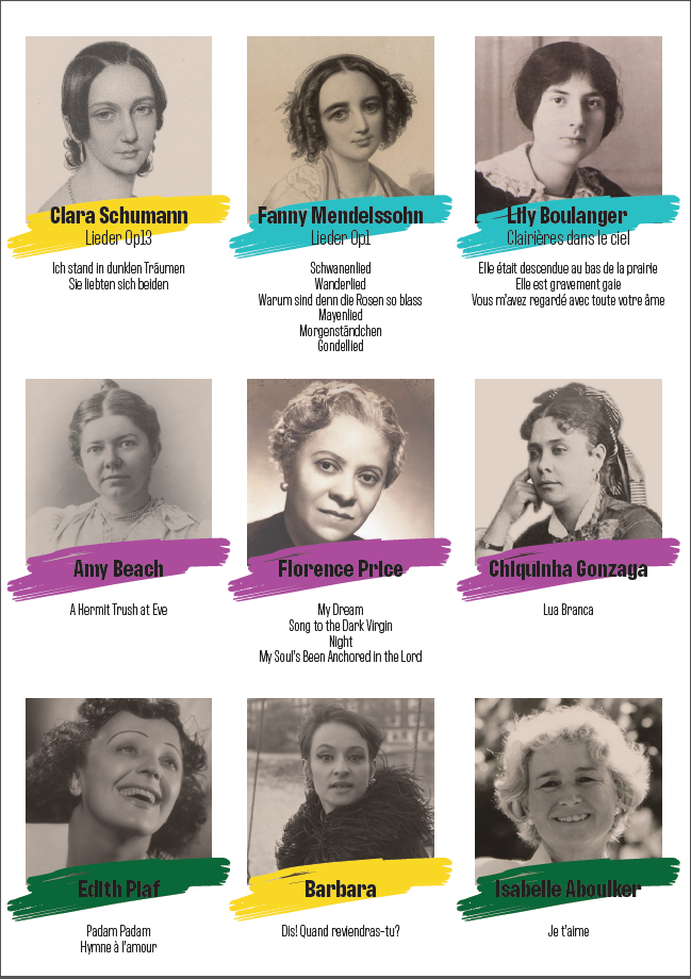

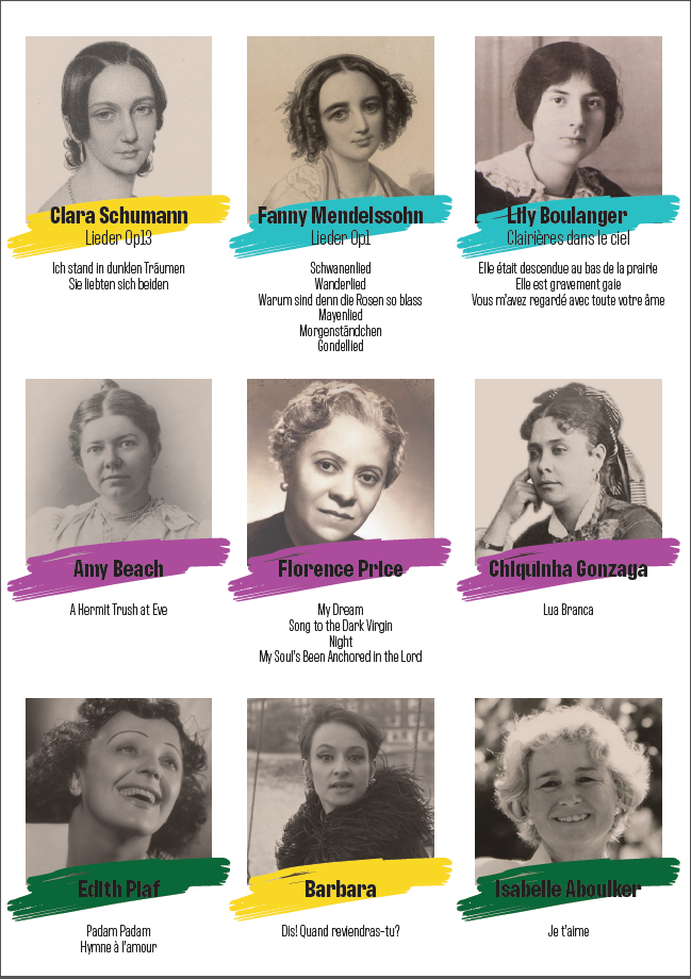

Her mother also instilled in her a sense of strength and independence. Florence Beatrice had made a decision to pursue music knowing that there only three successful American women composers who had their large-scale works performed by major symphony orchestras: Margaret Rutheven Lang, Helen Hopekirk and Amy Cheney Beach. It is quite an amazing realization that a few decades later Florence Price would be programmed along with Amy Beach as seen below:

Duo Elvire de Paiva and Pona & Joana Rolo perform works by women composers seen above.

Preparing for College

Florence Beatrice at the age of 14 was too young to go away to college. She faced the age challenge as well as the challenge of pursuing music as a female musician, and she faced the challenges of attending a predominantly white college.

Preparing for College

Her mother also instilled in her a sense of strength and independence. Florence Beatrice had made a decision to pursue music knowing that there only three successful American women composers who had their large-scale works performed by major symphony orchestras: Margaret Rutheven Lang, Helen Hopekirk and Amy Cheney Beach. It is quite an amazing realization that a few decades later Florence Price would be programmed along with Amy Beach as seen below:

Duo Elvire de Paiva and Pona & Joana Rolo perform works by women composers seen above.

Pursuing a Double Major at New England Conservatory

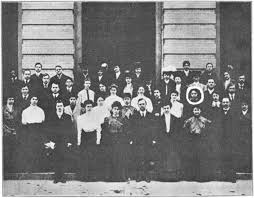

Florence B. Price attended NEC from 1903-1906. This photo represen

NEC

Florence B. Price attended her first year of college at the New England Conservatory at the age of 16. She enrolled in two majors, one in organ and one in piano. Price studied a litany of grueling courses such as Ear Training, Dictation, Harmony, Orgran construction, the History of Organ Literature, Counterpoint, Music History Orchestral Score Reading, among a number of other subjects.

The Normal Program was a program that Price studied which would provide training for music teachers in music education. Price focused on areas in teaching and in organ performance.

Composition at NEC

George Whitefield Chadwick, composer and professor at NEC, was a huge influence on Price. Chadwick was noted in particular for his attention and suggestions of use of Negro folk melodies and rhythms. When Czechoslovakian composer, Antonin Dvořák, arrived to the US in 1895, upon hearing the melodic, rhythmic and harmonic characteristics of the African American and the Native American folk music, he encouraged American composers to incorporate this rich material into their works. Price started to respond to her compositional instincts and began her compositional study.

Composition at NEC

Chadwick supported women composers and had accepted them into his studio. Price would utilize melodies from spirituals as well as rhythms and harmonies. Her use of these materials were supported by Chadwick.

Compositions Reflecting History

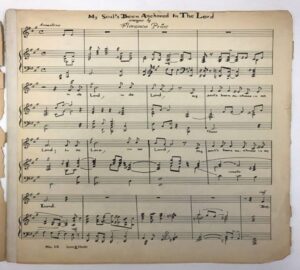

Taken at the Special Collections at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, Price’s title of this work reflects one of the main sources for meals for slaves.

Compositions

Many of Prices titles of compositions depict the history of the harsh realities of life that existed for the African American that was enslaved just a mere two decades before her birth.

The Cotton Gin, from In the Land O’ Cotton Suite for solo piano is a beautiful work with gentle rhythms that expose sentiments of the difficult days of slavery. One can hear the gentle ongoing action of the cotton gin. In the last movement of the suite, Dance, one hears the Juba dance. The Juba dance arrived to the US by slaves from West Africa. The dance was usually an impromptu dance in celebration or other ceremonies calling for clapping and stomping plus the slapping of hands on the body to act as instruments. Price grew up not far from Little Rock’s fourth largest cotton farm.

In the Land O’Cotton Suite won second prize in a composition competition sponsored by Casper Holstein, a black businessman from new York who offered fellowships and awards along with the Rockefeller and Rosenwald Fellowships. The award was announced in the Opportunity Magazine.

Studying at NEC

Florence was very active as a recitalist at NEC and was often featured in many of the evening recitals. She was invited to play in commencement and this is special because only 9 of a class of 50 were asked to perform on commencement.

Price received both the Teachers Diploma in Piano and a Soloists Diploma in Organ within just three years.

Study

Price was the only student in her class to receive two degrees. And as mentioned, both of these degrees were completed within three years, not four, the normal period of time for just one degree.

Price’s Class at New England Conservatory

Class

As an African American student, Florence Price broke a number of boundaries having graduated from NEC with the double degree and within three years. As well, her compositional world began to open up.

Florence Price as a Negro student at NEC

During the turn of the century in America, the Negro was suffering from many challenges ranging from those that lived in the south where the practices of the Jim Crow laws were strongly enforced to the North where many were in competitions for jobs with immigrants and foreigners. The conflict within the black race was increasingly becoming a challenge between the perceived lighter and darker complected as the lighter complected Negro was assumed to be smarter because there were more indications of white descent which translated as being smarter than the darker complected Negro. This would lead to jealousy and lack of support in addition to the usual racial components as a black from the counterpart white person. Read how Ms. Smith handled this situation with her daughter, Florence Beatrice at NEC:

Apartment

Ms. Smith paid for an apartment off campus so that her daughter would live by herself in a protected environment. As quoted from The Heart of a Woman by Rae Linda Brown, ” My grandmother didn’t want my mother to be a Negro so when she took her to Boston, she rented an expensive apartment with a maid and forced my mother to say her birthplace was not Little Rock but Mexico. “.

Born: April 9, 1887 – Little Rock, Arkansas

Died: June 3, 1953 – Chicago, Illinois

After Price received her diplomas from NEC she returned home to Little Rock and started teaching at Shorter College as she lived back with her parents.

Back Home

Teaching at Atlanta Clark University

After losing her father and having lost her mother as she disappeared, both within a two year period, Price accepted a position as chair at Clark Atlanta University in Atlanta, GA.

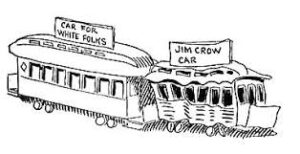

Colored Only

From the Smithsonian Magazine, written by Alex Palmer, this restored Pullman Palace passenger car, which ran along the Southern Railway route during the “Jim Crow’ era of the 20th century.

Colored Only

Read this very important article written by Alex Palmer here: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/segregated-railway-car-offers-visceral-reminder-jim-crow-era-180959383/

Life in Segregation

Segregation

The rise of violence in Little Rock increased exponentially with the growing impact of the Jim Crow Era. Price chose to leave her job in Atlanta and return to Little Rock, Arkansas.

Marriage between Florence B. Smith and Mr. Thomas Price

Marriage

This was a difficult time as Price lost her father in 1910 when she was only 23 years old. At the time of his passing, because of Jim Crow laws, her father lost most of his financial assets. Dr. Smith did not have much to leave but he left nothing for his son which with his disappearance, it is presumed that he slipped into white society and was not heard from by his immediate family members. With the financial difficulties at hand, Mrs. Smith decided to flee back to her home in Indianapolis. Because of her persistence in aligning as much as she could with the white community, it is presumed that she too slipped into white society and was never heard from by Florence Beatrice again.

In 1912 at the age of 26, Florence Beatrice marries Mr. Thomas Price.

The Train Ride to a New Life

After Florence Price’s father died, possibly in an attempt to put Little Rock behind her for a while, she left her hometown at the age of 23 to accept a prestigious teaching position as Head of the Music Department at Clark University in Atlanta. However, the only thing between Price and this new life of teaching at Clark was a gruesome train ride.

The Train Ride to a New Life

Florence Price was born in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1887. Her mother, Florence Irene Smith Nee Gulliver, was a schoolteacher in Indianapolis, and her father, James H. Smith was the only black dentist in the city. The family was decently well-off with Florence Price’s father having high-profile clients and her mother serving as the secretary of the International Loan and Trust Company and owning a restaurant and real estate.

After Florence Price’s father died, possibly in an attempt to put Little Rock behind her for a while, she left her hometown at the age of 23 to accept a prestigious teaching position as Head of the Music Department at Clark University in Atlanta. However, the only thing between Price and this new life of teaching at Clark was a gruesome train ride. One of the most insidious acts of discrimination was the treatment of African Americans on the railroad. The salespeople on the train had a rude and condescending attitude toward African Americans and they also tried to cheat and confuse African Americans in an attempt to charge them higher prices for their tickets. The accommodations were noisy, dirty, smelly and according to Du Bois, the train stopped beyond the covering with no step to help passengers get on the train and the accommodations were less than the oldest car in service with filthy floors, windows, and toilets.

For a professional woman of Price’s social standing, she must have barely tolerated the degrading conditions she experienced during the train ride to Atlanta especially as she grew up in a well-off household. It goes to show that despite all of the accomplishments African Americans made in their lives, they were still degraded and treated poorly by white people.

Author: Vikash Rivers

Reference: “The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price” by Rae Linda Brown

A New Woman On Campus

After the dreadful train ride, Price arrived at Atlanta, and Clark University welcomed her with open arms. Seeing as most of the teachers at Clark were white, Clark felt privileged to have such a well-educated African American woman on campus. The faculty and administrators of the university felt strongly about their cultural life, so they held a program of rhetoric once a week in the chapel to provide an opportunity for students to hear and recite the works of classical authors, poets, and playwrights.

A New Woman On Campus

After the dreadful train ride, Price arrived at Atlanta, and Clark University welcomed her with open arms. Seeing as most of the teachers at Clark were white, Clark felt privileged to have such a well-educated African American woman on campus. The faculty and administrators of the university felt strongly about their cultural life, so they held a program of rhetoric once a week in the chapel to provide an opportunity for students to hear and recite the works of classical authors, poets, and playwrights.

The Music department was an integral part of the rhetorical program and of 479 enrolled students, 40 of them took music classes. As head of the Music department, Price’s appointment as composer, artist-in-residence, and music teacher was important to the cultural life of the university. Under her leadership, the students performed works of Beethoven, Mozart, Chopin, and Brahms, and vocal performances of ballads, parlor music, and operatic arias were common. She regularly gave organ and piano recitals, and she brought nationally recognized artists to the campus to give concerts. It was through these artists that students learned to appreciate European concert repertoire and also music by their own race.

In addition to the students, the performers, particularly the instrumentalists who were locked out of most concert halls because of their race benefitted because it provided them with the opportunity to perform.

The students lived vicariously through these artists who continued to thrive and survive despite their difficulties. Later on, these performers became teachers and served as mentors who often provided scholarships to aspiring musicians.

Under Price’s leadership, many students and performers benefitted from the rhetorical program which allowed them to practice their musical skills in the real world and also hear music from some of the most prominent African American musical artists where they would have otherwise never had the opportunity to.

Author: Vikash Rivers

Reference: “The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price” by Rae Linda Brown

A Love Life Turned Bitter

While Florence Beatrice was teaching at Clark, her love interest was a young, handsome attorney named Thomas Jewell Price. Florence Beatrice eventually returned to Little Rock in the summer of 1912 and got married to Thomas Price by a justice of the peace. Initially, their marriage was going fine, until things took a turn for the worst.

A Love Life Turned Bitter

While Florence Beatrice was teaching at Clark, her love interest was a young, handsome attorney named Thomas Jewell Price. Price had moved from Washington D.C. to Little Rock where the Price and Smith family became friends. Florence Beatrice eventually returned to Little Rock in the summer of 1912 and got married to Thomas Price by a justice of the peace. They settled in a middle-class, predominantly black neighborhood where their neighbors were also professionals. They were both active in the Little Rock community where Florence Price was both president and director of the Little Rock Club of Musicians.

Soon after they were married, the Prices started a family with their firstborn child being a boy named Thomas Jr. Price was proud of her son and she wrote a song called “To my Little Son” that captured the love and bond that she shared with her son. The Prices then had two other daughters named Florence Louise and Edith Cassandra. After the children were born, Perry Quinney moved in with the Price family and acted as a caretaker for the children which gave Price some time to teach, compose and be active in outside musical activities.

Furthermore, during the Price family’s initial years in Chicago, things seemed stable, but when the Great Depression hit, Thomas Price went for long stretches without working which put a lot of financial strain on the family. This financial strain took a toll on Thomas Price and his frustration and anger led to violence when he struck Florence with his fist, slapped her face, and knocked her down. On another occasion, he even threatened to kill her. As a result, Florence Price filed for divorce from Thomas Price and she won the case and she got everything she wanted including custody of her children, $25 a week in alimony and child support, and an additional $100 in court fees.

Florence Price was now free from the mental, emotional, and physical abuse that she had endured for so long. She eventually met another man named Pusey Dell Arnet and married him one month after the divorce most likely for financial security.

Author: Vikash Rivers

Reference: “The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price” by Rae Linda Brown

Escape to the Land of Opportunity

Through the late 1920s, the racial tension in Little Rock was getting worse. These tensions even dampened the professional aspirations of Florence Price as she was denied admission from the Arkansas Music Teachers Association because of her skin color despite her impeccable academic and teaching credentials. As time went on Little Rock became more frightening and unsafe as African Americans were being lynched and left without police protection. After a white child was allegedly killed by an African American man, the white community was out with a vengeance, so they threatened to kill Florence Price’s youngest daughter. Fearful for their lives, the Price family fled to Chicago because it was considered the land of opportunity for many African Americans.

Escape to the Land of Opportunity

Through the late 1920s, the racial tension in Little Rock was getting worse. These tensions even dampened the professional aspirations of Florence Price as she was denied admission from the Arkansas Music Teachers Association because of her skin color despite her impeccable academic and teaching credentials. As time went on Little Rock became more frightening and unsafe as African Americans were being lynched and left without police protection. After a white child was allegedly killed by an African American man, the white community was out with a vengeance, so they threatened to kill Florence Price’s youngest daughter. Fearful for their lives, the Price family fled to Chicago because it was considered the land of opportunity for many African Americans.

When Price and her family moved to Chicago, they found a vibrant and culturally rich community where African Americans were thriving in all of the arts such as literature, poetry dance, theatre, the visual arts, and especially music. Additionally, the Grand Theater had become notable for hosting some of the biggest names in jazz and blues. Since Price was a deeply spiritual person who attended church all her life, she affiliated herself with Grace Presbyterian Church where she performed contemporary music including organ and choral music. Price also became one of the most active members of the R. Nathaniel Dett Club where she held various offices including the chair of the composition committee. Even though she was part of the Dett Club, she was equally active and more visible through her activities in the Chicago Music Association where she met the most distinguished members of the black community.

Both Price and her husband became active professionally, socially and took advantage of everything the city had to offer. She had set up a private piano studio in her home and since her children were older, she spent much of her time composing. She discovered that she had a gift for writing teaching pieces for children and she once again pursued the Arthur P. Schmidt Co. in Boston about publishing nine of her teaching pieces for piano. All of the compositions were accepted, but they were never published. Instead, they were issued in various other ways.

Despite the challenges back in Little Rock as racial tensions got worse, Florence Price persisted and made a better life for herself in Chicago by taking advantage of everything the city had to offer and applying herself.

Author: Vikash Rivers

Reference: “The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price” by Rae Linda Brown

Mommie Dearest

Once when Florence Beatrice was a young girl, she was invited to participate in a wedding. Later Beatrice’s daughter explained, “My mother was a Bridesmaid and her mother forced her to wear such an elaborate dress that she outshone the bride. This hurt my mother very much, but everyone understood and didn’t blame her”! This moment described a sad reality that even though Beatrice’s mother was great in some regards, it also shows that she was flawed to some extent. This is one of many challenges Beatrice had to face. It was what is known in common parlons as a flex. A display of wealth to show that young Beatrice, and by extension, her mother, wasn’t of the same class as the others in attendance.

Mommie Dearest

Once when Florence Beatrice was a young girl, she was invited to participate in a wedding. Later Beatrice’s daughter explained, “My mother was a Bridesmaid and her mother forced her to wear such an elaborate dress that she outshone the bride. This hurt my mother very much, but everyone understood and didn’t blame her”! This moment described a sad reality that even though Beatrice’s mother was great in some regards, it also shows that she was flawed to some extent. This is one of many challenges Beatrice had to face. It was what is known in common parlons as a flex. A display of wealth to show that young Beatrice, and by extension, her mother, wasn’t of the same class as the others in attendance.

It was very clear that Beatrice’s mother Mrs. Florence Smith disassociated herself from the negro race. She was a white-passing individual, who was of the ideology that this made her better than the other negroes. She would frequently try to imprint this same ideology on her daughter Beatrice, making her pass as Mexican when attending school at the New England Conservatory. Now one of the top music schools in America. Records show that Beatrice began school passing as a Little Rock native and when her third and final year came about, she changed her hometown to Pueblo Mexico. This is most likely to remove any chance of the school holding her back from receiving her double degree, as this took place in the Jim Crowe error of the nation’s history. But what is abundantly clear, is that after this occurrence, as shown extensively in her compositions which have been crafted and seasoned with the history and experiences of an African American, Florence Price would never “Pass” again.

Author: Micah Omari Mitchell

Reference: “The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price” by Rae Linda Brown

The Little Rock Return

Florence Beatrice returning to Little Rock after Graduation from the New England Conservatory was an interesting decision. However, it did make sense. There was almost no chance that she would get a Teaching Job in the North. But there was also a chance that Price returned because she felt a sense of responsibility to give back to the community that made her the woman she was. She wanted to give back to her community, the negro community in Little Rock. At this, when Florence Price decided to become a teacher, educating Little Rock’s Black community the pay for Black teachers was $30.36 per month as opposed to the pay for white teachers which was $40.52.

The Little Rock return

Florence Beatrice returning to Little Rock after Graduation from the New England Conservatory was an interesting decision. However, it did make sense. There was almost no chance that she would get a Teaching Job in the North. But there was also a chance that Price returned because she felt a sense of responsibility to give back to the community that made her the woman she was. She wanted to give back to her community, the negro community in Little Rock. At this, when Florence Price decided to become a teacher, educating Little Rock’s Black community the pay for Black teachers was $30.36 per month as opposed to the pay for white teachers which was $40.52.

Florence Beatrice’s First Job as she returned to Little Rock was at the Cotton Plant-Arkadelphia Academy in Cotton Plant Arkansas. This was a school supported by the white presbyterian church as a school for negroes that boasted a liberal arts-based secondary school curriculum. This is where she met Neumon Leighton, a white musician and lifelong friend of hers. After her tenure at Cotton Plant, she began working at Shorter College in North Little Rock. An appointment she held from 1907-1910. It was founded by the African Methodist Episcopal Church and Arkansas Baptist College. While working here, Florence would play the organ for services which were every week, as this by every right, was a Christian School. But what’s more, Florence would also put on performances for the student and faculty body for the cultural enrichment of the school.

This shows me that Florence Beatrice was a role model. For someone to have gone to a better place and achieved excellence, and to return to whence she came for the betterment of her community is nothing short of inspirational. The little things such as performing for the youth in her school, a world-class performer and composer, performing for her group of students to give them a sense of pride and culture in their institution is simply an act of selflessness.

Author: Micah Omari Mitchell

Reference: “The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price” by Rae Linda Brown

The Tutor

After marrying Thomas Price, Florence Price moved back to Little Rock. She had ceased her college teaching life but not teaching as a whole. She would, in her spare time from taking care of her three children, teach private Piano and Violin lessons. She quickly became one of Black Little Rocks’ most sought-after music teachers. She had a reputation for giving a very solid background to her students in Piano and was known for being firm and well-liked. Each of her students was given two half-hour lessons each week, where they would perform piano literature and also did lessons in musical transposition.

The Tutor

After marrying Thomas Price, Florence Price moved back to Little Rock. She had ceased her college teaching life but not teaching as a whole. She would, in her spare time from taking care of her three children, teach private Piano and Violin lessons. She quickly became one of Black Little Rocks’ most sought-after music teachers. She had a reputation for giving a very solid background to her students in Piano and was known for being firm and well-liked. Each of her students was given two half-hour lessons each week, where they would perform piano literature and also did lessons in musical transposition.

In fact, Florence Price wrote her own Piano studies. All with the fanciest of titles that would make children interested. Some of these were “Brownies on the Seashore,” a study of three sharps (the most advanced key signature in the series); “Brung the Bear”, which stresses the five-finger hand position and the use of the thumb on the black keys, “The Froggie and the Rabbit”, is a study in Rhythm and “Golden Corn Tassles” in an exercise in the contrast between legato and staccato.

This is another example of Florence Price wanting to better her community. Creating simplified exercises for her students with creative names, some of which link to the history of blacks in America, like golden Corn Tassles which were slave food, is a shining example of the type of work she was trying to accomplish. Even in her free time, Florence couldn’t help but educate the uneducated.

Author: Micah Omari Mitchell

Reference: “The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price” by Rae Linda Brown

The Chicago Professional

The Price family settled at 3835 Calumet St. in the heart of the Black Belt in Chicago. Price set up a private piano studio in her home, and with her children a little older, she spent a lot of time composing music. This was the most productive period of Florence Price’s life as she found that she had a gift for composing instructional pieces for kids. She primarily composed for Piano but also composed for violin and organ with piano accompaniment. This is how she created a niche for herself and found it to be a profitable endeavor. She actually secured publishers with ease such as G. Schirmer, McKinley, Theodore Presser, Gamble Hinged Music, Carl Fischer, and Clayton F. Summy.

The Chicago Professional

The Price family settled at 3835 Calumet St. in the heart of the Black Belt in Chicago. Price set up a private piano studio in her home, and with her children a little older, she spent a lot of time composing music. This was the most productive period of Florence Price’s life as she found that she had a gift for composing instructional pieces for kids. She primarily composed for Piano but also composed for violin and organ with piano accompaniment. This is how she created a niche for herself and found it to be a profitable endeavor. She actually secured publishers with ease such as G. Schirmer, McKinley, Theodore Presser, Gamble Hinged Music, Carl Fischer, and Clayton F. Summy.

Florence Price and McKinley established a relationship, and they published over 25 of her compositions for children over her career. Some of these were Playful Rondo (1928), Mellow Twilight (1930), and others. Also, a composition of hers At the Cotton Gin, A Southern Sketch had been submitted to a competition by her husband unbeknownst to her. This submission won a cash prize and a publishing contract with Schirmer was to last many years.

In addition to this, Florence also wrote popular music typically under the pen name Veejay, for radio commercials and to be sung in theatres and musicals throughout the city. Many of her compositions for popular music took the tin pan alley format. This means the verse describes a sentimental or tragic format and is followed by a chorus that expresses a reaction to the situation and provides the song’s melodic hook.

Wherever Florence Price would go she would create. As shown by the aforementioned compositions, her passion for teaching never ceased, rather, it metamorphosized. Moreover, Florence’s creativity and love for the stage and performing also endured, even with being on the move seemingly constantly, and dealing with three children, this woman kept doing what she loved to do. That is what Florence Price represents.

Author: Micah Omari Mitchell

Reference: “The Heart of a Woman: The Life and Music of Florence B. Price” by Rae Linda Brown

Segregation’s Affects

Segregation was the order of the day and racial tensions began to mount in the city. Price was unable to find employment and, after being refused admission to the all-white Arkansas Music Teachers Association, she founded the Little Rock Club of Musicians and taught music at the segregated black schools. Little Rock had been a comfortable city for Black residents, but as racial problems began to develop resulting in a lynching, she moved with her husband, Attorney Thomas J. Price (whom she married in 1912) and their two daughters, to Chicago in 1927.

Shortly after arriving in Chicago, Price joined the R. Nathaniel Dett Club of Music and the Allied Arts (named for the black composer of Canadian descent) and did additional study at the American Conservatory of Music, Chicago Teachers College, Central YMCA College, the University of Chicago and Chicago Musical College (now Chicago College of Performing Arts of Roosevelt University) as a student in composition and orchestration with Carl Busch and Wesley LaViolette, graduating in 1934.

It was at Chicago Musical College that Florence Price met baritone Theodore Charles Stone, a member of the Chicago Music Association who later served as its President from 1954 to 1996).

The Chicago Music Association (CMA) had been established March 3, 1919 by Nora Douglas Holt, then the classical music critic for The Chicago Defender, in order to provide performance venues for classically-trained “Negro” musicians who were, by tradition, denied performance opportunities in major concert halls and on opera stages throughout the country. In July, 1919, musicians from Washington, D. C., met with the newly-organized CMA in Chicago at Bronzeville’s historic Wabash Avenue Y.M.C.A. and organized the National Association of Negro Musicians, Inc. (NANM); CMA became the first branch and awarded its first scholarship prize to Miss Marian Anderson of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is significant to note here that these meetings were held during a horrific race war occurring less than three miles away at the 31st Street Beach and gunshots could be heard through the open windows of the meeting hall.

Segregation’s Affects

Segregation was the order of the day and racial tensions began to mount in the city. Price was unable to find employment and, after being refused admission to the all-white Arkansas Music Teachers Association, she founded the Little Rock Club of Musicians and taught music at the segregated black schools. Little Rock had been a comfortable city for Black residents, but as racial problems began to develop resulting in a lynching, she moved with her husband, Attorney Thomas J. Price (whom she married in 1912) and their two daughters, to Chicago in 1927.

Shortly after arriving in Chicago, Price joined the R. Nathaniel Dett Club of Music and the Allied Arts (named for the black composer of Canadian descent) and did additional study at the American Conservatory of Music, Chicago Teachers College, Central YMCA College, the University of Chicago and Chicago Musical College (now Chicago College of Performing Arts of Roosevelt University) as a student in composition and orchestration with Carl Busch and Wesley LaViolette, graduating in 1934.

It was at Chicago Musical College that Florence Price met baritone Theodore Charles Stone, a member of the Chicago Music Association who later served as its President from 1954 to 1996).

The Chicago Music Association (CMA) had been established March 3, 1919 by Nora Douglas Holt, then the classical music critic for The Chicago Defender, in order to provide performance venues for classically-trained “Negro” musicians who were, by tradition, denied performance opportunities in major concert halls and on opera stages throughout the country. In July, 1919, musicians from Washington, D. C., met with the newly-organized CMA in Chicago at Bronzeville’s historic Wabash Avenue Y.M.C.A. and organized the National Association of Negro Musicians, Inc. (NANM); CMA became the first branch and awarded its first scholarship prize to Miss Marian Anderson of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It is significant to note here that these meetings were held during a horrific race war occurring less than three miles away at the 31st Street Beach and gunshots could be heard through the open windows of the meeting hall.

Ted Stone encouraged Price to join CMA where she met organist Estella Bonds and her young daughter, Margaret, who would later become Florence’s student. Stone was the first black who would later study at The Sibelius Institute in Helsinki, Finland after having sung for Marian Anderson’s accompanist, Kosti Vehanen, a colleague of Jean Sibelius who awarded Stone a scholarship. The outbreak of the World War II in Europe would force Stone to return to Chicago in 1939 where he reunited with CMA and resumed his career as a classical concert singer, music promoter and journalist writing for The Chicago Bee and The Associated Negro Press (both now defunct), The Chicago Defender, at that time the oldest Black-owned daily newspaper (est. 1905) and The Chicago Crusader, the oldest Black-owned weekly newspaper (est. 1940).

Florence Price’s career flourished after the move to Chicago. It was around 1928 when the G. Schirmer and McKinley publishing companies began to issue her songs, piano music, and especially her instructional pieces for piano. She filed for divorce from Thomas Price in 1928 and she and the children moved in with her student and friend Margaret Bonds. She gave music lessons at home and at T. Theodore Taylor’s School of Music located in the Abraham Lincoln Centre Community Service Agency, 700 E. Oakwood Blvd. in Chicago’s historic Bronzeville Community (now occupied by Northeastern Illinois University’s Center for Inner City Studies) and composed more than 300 works including symphonies, organ works, piano concertos, works for violin, arrangements of spirituals, art songs, and chamber works.

Florence Price’s friendship with Margaret Bonds gained national recognition and performances for both. Price and Bonds had submitted compositions for the 1932 Wanamaker competition with Price winning first prize for Symphony in E minor and second prize for her Piano Sonata. Bonds won third prize for a vocal work. Price’s works were performed in concerts held in churches and black social and cultural clubs by chamber ensembles, solo artists, her own Treble Clef Glee Club and by the Florence B. Price A Cappella Chorus conducted by Grace W. Thompkins. A number of Price’s orchestral works were played by the Chicago Women’s Symphony and the WPA Symphony of Detroit.

Florence Price became friends with Marian Anderson, who had sung Price’s spiritual arrangement “My Soul’s Been Anchored in the Lord” and Schubert’s “Ave Maria” in an international broadcast from Prague on May 6, 1937 (so noted in CMA’s archives), composer William L. Dawson of Tuskegee Institute, Will Marion Cook who had attended New York City’s National Conservatory while Antonin Dvorak was its president, Abbie Mitchell, Langston Hughes and many others.

Professor De Lerma adds “As a single person, she earned a living from the sales of her piano works and, under the pseudonym of Vee Jay, as composer of popular songs. She also played organ for the silent films and orchestrated for WGN radio. Additional performances were secured with the U. S. Marine Band, the Michigan W.P.A. Symphony, the Forum String Quartet, the Detroit W.P.A. Concert Band, the Chicago Club of Women Organists, the Illinois Federation of Music Clubs, the Musicians Club of Women (Chicago), the Brooklyn Symphony, the Bronx Symphony, the Pittsburgh Symphony, the Chicago Chamber Orchestra and the New York City Symphonic Band.

Marian Anderson began singing Price’s arrangement of the spiritual My Soul’s Been Anchored in the Lord regularly on her concerts which always concluded with Negro Spirituals. She then performed Price’s original setting of the Langston Hughes poem cycle Songs to a Dark Virgin which a Chicago Daily News reviewer called “one of the greatest immediate successes ever won by an American song.” The Hughes song cycle was published in 1941 and other leading black vocalists, among them Roland Hayes and later Leontyne Price, began to sing Price’s vocal music. Among her admirers was composer John Alden Carpenter (whose Concertino for Piano and Orchestra had been performed by Margaret Bonds on the 1933 history-making Century of Progress Exposition concert) who sponsored her for membership in the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Performers (ASCAP).

Price continued to compose throughout the 1940s and early 1950s, penning two concertos for violin and orchestra, two additional symphonies, one of which, Symphony No. 2, has apparently been lost. She gained recognition from as far away as England where conductor Sir John Barbirolli commissioned her to compose a suite for string instruments which had its premiere with the famed Hallé Orchestra in Manchester. Some of Price’s output was written for specific instruments; she continued to write art songs and music for choruses that performed on radio station WGN. She continued to arrange spirituals for solo voice and composed pieces for organ that were performed by organists in the many black churches of Chicago. She even served a term as Recording Secretary of CMA whose members gave constant encouragement and support. In 1997 Calvert Johnson, organist at Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Georgia recorded seventeen of Price’s organ works and performed them in a 1999 CMA-sponsored recital on the historic Kimball Organ at Chicago’s First Baptist Congregational Church.

In 2010 the Center for Black Music Research (CBMR established by researcher Samuel Floyd in 1983) commissioned Trevor Weston, an associate professor of music at Drew University, to reconstruct the long-lost orchestral score for Price’s Concerto in One Movement for Piano and Orchestra in order to perform the concerto and release an album of the composer’s work which would become the third issue in the CBMR series, “Recorded Music of the African Diaspora.”

Dr. Weston studied three of Price’s piano rehearsal scores for the concerto and read articles about her written by Rae Linda Brown, music professor at the University of California-Irvine and foremost Florence B. Price researcher and biographer. Dr. Brown said Weston’s name surfaced early on as someone who understood the history of American music, one who would be able to understand what a symphony orchestra sounded like in 1934. She added “We can uphold Trevor’s score as authentic. He upheld it as a piece of African-American history, a very important piece of history. He stayed true to Florence Price’s voice” which is a combination of the romantic style coupled with the black cultural heritage.

Florence Price’s reconstructed Concerto in One Movement for Piano and Orchestra with Karen Walwyn, pianist and Symphony No. 1 in E Minor with Leslie B. Dunner conducting the New Black Music Repertory Ensemble were performed at Chicago’s Harris Theater for Music and Dance on February 17, 2011, to great critical acclaim, thanks to CBMR Executive Director Monica Hairston O’Connell, Deputy Director Morris Phibbs and staff for their perseverance and dedication in keeping to the Center’s mission. The CD recording was released by Albany Records later that same year. In 2001 The Women’s Philharmonic, Apo Hsu, Artistic Director and Conductor had recorded Price’s The Oak (1934), Mississippi River and Symphony No. 3 in C minor (1940). A 2008 reissue of that CD by Koch International Classics is currently available at various outlets.

Dominique-René de Lerma writes that Florence B. Price’s materials are held within the Special Collections of the University of Arkansas-Fayetteville where they were presented in 1974 by Price’s daughter Florence Price Robinson, and at the Library of Congress. Included in the Arkansas collections is correspondence to and from John Alden Carpenter, Roland Hayes, Eugène Goossens, Harry T. Burleigh, and others.

While planning a trip to Europe, Florence B. Price died of a stroke on June 3, 1953 in Chicago, her adopted city that she had come to love; a city that, in 1964, named an elementary school for her as its own recognition of her legacy as a Chicago musician and an important black composer (but, unfortunately, scheduled for closing by The Chicago Public Schools in 2011); and a city, a nation, a world that deserves to experience her music and that of her colleagues and contemporaries; music that Antonin Dvorak would affirm as authentic; music that had as its basis those slave songs that survived the middle passage to become firmly entrenched in the American musical landscape.

Mississippi River: “The River and Those Dwelling Upon its Banks” was written in 1934 and dedicated to Arthur Olaf Anderson, one of Price’s mentors and head of the Theory Department at Chicago’s American Conservatory of Music.

The work replicates a boat cruising down the Mississippi River and experiencing life along its banks. The opening section, like Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 1, depicts the awakening of dawn, but in this case, along river banks. Section 2 introduces a Native American theme scored for Indian drum, timpani, marimba, and other percussion instruments. In section 3, four Negro spirituals Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen, Stand Still, Jordan, Go Down, Moses and Deep River and original work by Price are mixed with traditional tunes of the day, River Song, Lalotte, and Steamboat Bill. The suite concludes with a layering of the melodies, alternately stacked one upon the other, with the spiritual Deep River the most dominant of all.

Florence Price Recording Project

Dr. Walwyn looks forward to completing the first of four volumes of music for solo piano and some chamber work of Florence Price. She anticipates the completion of the first volume by July 2021. Updates will be announced here at our Florence Price News.

Most of the works to be recorded will be premiere recordings. It is a very exciting project, and we hope that you will check back to see how things are coming especially as we get closer to Florence’s birthday, April 9.

We are accepting donations towards the recording project.